|

Landing Craft Support Squadron -

Gun, Flak and Rockets.

Sicily, Italy, Normandy & Walcheren

Support landing craft, in the form of

Landing Craft Gun (LCGs),

Landing Craft Flak (LCFs) and

Landing Craft Rocket (LCRs),

provided fire power to soften up entrenched enemy positions on and near

the landing beaches in advance of

the initial assault troops.

Furthermore, LCFs & LCGs provided troop and tank carrying landing craft with

on going cover against enemy attack from land, sea or air

as well as shelling inland targets identified by the Army that were within

range. This account provides an insight into the establishment of a support

squadron and its deployment. Support landing craft, in the form of

Landing Craft Gun (LCGs),

Landing Craft Flak (LCFs) and

Landing Craft Rocket (LCRs),

provided fire power to soften up entrenched enemy positions on and near

the landing beaches in advance of

the initial assault troops.

Furthermore, LCFs & LCGs provided troop and tank carrying landing craft with

on going cover against enemy attack from land, sea or air

as well as shelling inland targets identified by the Army that were within

range. This account provides an insight into the establishment of a support

squadron and its deployment.

It was written by Chief Engine Room Artificer (CERA)

Robert Wallace-Sims, who was attached to Combined Operations Command for nearly

3.5 years before returning to the 'regular' Navy after the war.

[Photo; the author, Robert Wallace-Sims with his

wife and son].

Early Training

It was Christmas 1942 and six weeks leave had passed quickly. I reported

back to the Royal Naval

Barracks, Portsmouth

on February 2nd. The next day, I attended the Diesel School at Chatham for a three weeks course on Paxman

diesels engines, after which I was transferred

to HMS Dundonald, a Combined Operations

training establishment in Troon, Ayrshire, where Landing

Craft Tank (LCTs) were commissioned and worked up before

being released for joint amphibious training exercises with

the Army.

After three weeks in Troon, during which time I don't

remember doing any useful work, I reported to Harland and Wolff in Belfast to take

over the maintenance of the 8th LCT Flotilla. There was no

accommodation available on site so I was billeted with

a delightful elderly lady, who suggested my

wife should join me. Although

Belfast was a prohibited area, I obtained the necessary travel documents

and she arrived shortly thereafter.

The Landing Craft

Meantime, I reported to the Flotilla Officer and found

an unusual degree of secrecy. There were twelve LCTs in Harland and Wolff’s

yard

undergoing conversion to Landing Craft Guns (LCGs). The work

required a new deck over the

existing tank deck and converting the resultant

enclosed space to magazines and

living quarters. On the deck above, two 4.7 inch guns

were mounted forward of the

bridge. Twelve more craft were undergoing similar conversions in London, whilst

elsewhere, twelve more were being

converted to Landing Craft Flack (LCFs) and a further

12 to Landing Craft Rockets (LCRs).

The whole would eventually join forces as a support squadron to

cover landings. The maintenance crew consisted of myself, 4 Engine Room

Artificers (ERAs), 2 Motor Mechanics, 4

Stokers, a Shipwright, two Joiners, an Ordinance Artificer, a

Seaman Gunner, an Electrical Artificer and three wiremen for the electrics.

20 in all, whose collective job was to maintain all twelve craft in operational condition.

I found my maintenance crew

were either hostilities only (HOs) or Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve

(RNVR). This was my first experience

of RNVR Officers and HOs and they were a fine and competent crowd.

None of the maintenance staff, including the Engineer Officer, who was a Croxley

Heath dirt track rider, had more than six months service. Their

knowledge of Paxman diesels was as much as they had

managed to learn on the same training course I had

attended.

The first two

completed craft left Belfast at the end of

March 1943 for Falmouth but they had a serious design flaw, which would prove to have

fatal consequences. The forward end of the tank deck had been left open with the

bow door and winches in a fully usable condition. The tank deck of an LCT had a series of

drains running down to a duct keel, which could be pumped out. Although

watertight bulkheads had been fitted, the drains had not been sealed off so, in

effect, there

was no real water

tightness. Off Milford Haven, the two craft ran into very heavy

weather and sea-water was shipped over the bows,

which found its way into the duct keel and up into the mess decks and magazines.

The one bilge pump in each craft was overwhelmed by the amount of water and

consequently both craft foundered with most of

their crews. tightness. Off Milford Haven, the two craft ran into very heavy

weather and sea-water was shipped over the bows,

which found its way into the duct keel and up into the mess decks and magazines.

The one bilge pump in each craft was overwhelmed by the amount of water and

consequently both craft foundered with most of

their crews.

[Map courtesy of Google. 2017].

Orders came through for the doors to be welded up and the deck to

be fully covered in. The result was a very strong, stable and sea worthy craft

but it was mid-May before the whole squadron arrived in Falmouth.

The

Mediterranean

One

ship from the 6th Flotilla joined us, making

our flotilla 11 strong. From Falmouth we sailed in convoy

with a large number of LCTs to Dijelli

in North Africa, where the Squadron

was split in two, half remaining in Dijelli, while

the others moved further east to Sousse.

After about five weeks, we

moved to Malta, arriving there in early July. This was my first visit to Malta since

Christmas 1941. German bombers had caused colossal

damage but, by some miracle, all the pubs we had

used then were still standing! One

ship from the 6th Flotilla joined us, making

our flotilla 11 strong. From Falmouth we sailed in convoy

with a large number of LCTs to Dijelli

in North Africa, where the Squadron

was split in two, half remaining in Dijelli, while

the others moved further east to Sousse.

After about five weeks, we

moved to Malta, arriving there in early July. This was my first visit to Malta since

Christmas 1941. German bombers had caused colossal

damage but, by some miracle, all the pubs we had

used then were still standing!

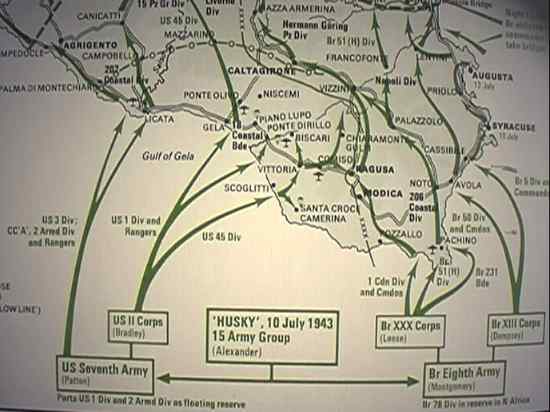

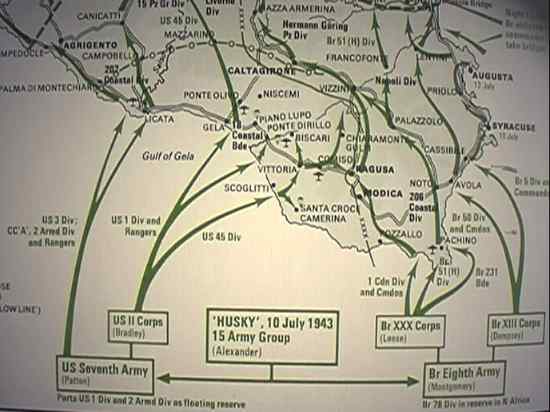

On July 9th, we moved out for the invasion of Sicily, arriving

off Regussa in the early hours of the 10th. We were in the lead as we approached

the landing beaches, followed by

masses of landing craft and ships of all shapes and sizes. Our LCGs went in with

all guns firing, while behind us the Rocket craft released their projectiles

from about

two miles off shore. The sight and sound of salvos of about 200 or more rockets from each

craft was awesome. They carried about 600 rockets

fired in banks of about 200. Having exhausted the 600, they retired to reload.

Below are the diary notes of an unknown veteran, which gives some sense of the

day's events.

Fri 9th July;

Stand by call to action stations.

Sat 10th July;

02.25 All's well. Flashes of AA fire from the beach. Beach well in sight,

cruisers and destroyers steaming on starboard beam.

02.35 All's well. Beach lit up by star shells. AA fire. Waiting to go in.

First wave of RM Commandos in LCG 3 believed gone in.

02.45 Our wave ready to go in, LCGs 9 & 10 with Canadians. LCG 3 just going in.

RAF still carrying out softening process.

03.00 No action as yet. Bombing and AA fire still active.

03.15 Moving into beach on port side. A’s and M’s loaded with RM Commandos

disappear in darkness towards beach.

03.30 Standing by to fire. Steady bombing still in progress. Range approx. 2

½ miles, 4000 yards.

03.45 Still moving in, covering port side of landing.

04.00 No shelling as yet. Intensified bombing still in progress. Range

approx. 4000 yards.

04.25 All guns loaded with reduced charges. Exchange of fire between MLs and

machine gun posts. Still closing with beach. Range 3500 yards.

04.30 Prepare to fire on machine gun posts from which tracers are pouring.

Range 1000 yards. Dawn is now breaking. Troops still pouring in.

04.35 Manoeuvring for covering fire and bombardment. No sign of any action

against ships yet.

04.40 Heavy smoke screen covering island. No shots fired at us as yet.

Rocket ships fired salvos and cleared machine gun posts.

04.45 Dawn has broken. Everything is clear. Destroyer fires two salvos and

then withdraws. Battery opens up at us. A large number of ships on the

horizon. Still training guns on target but still no shelling. Shots straddle

ship and make it shake. Enemy shore batteries firing at LCGs.

04.55 Begin firing in reply to enemy guns. Enemy guns silenced. Bridge

reports ammunition dump hit. Clear daylight, action well under way.

Expecting next shot to hit us. LCG firing closer to beach. LCAs standing off

beach. Troops pouring in. Shelling growing strong.

05.20 LCG 9’s gunfire effective.

05.30 Not much reply from the enemy, must be engaged by troops. Odd shots

dropping by craft. Many of our planes visible. Enemy battery silenced by us.

Complimented by craft coming alongside. Fires starting on shore, landing

craft standing off. Troops pouring in – 8th Army.

05.40 Resistance not heavy, it appears that aircraft supported overhead.

Pongos being ferried ashore. Shelling still continued, enemy guns silenced.

05.50 No important developments. Tanks, troops and amphibians still

streaming ashore. Bursts of Bren fire on shore.

07.45 Town appears to be taken. Fighting continues but not very heavy.

Machine gun fire coming from hills. Large explosion in water, just off

beach.

08.00 No further developments. Expecting enemy naval forces. We are now

lying 800 yards off the landing beach, 200 yards off rocky point. Water is only

25 feet deep, too shallow for LCIs to beach. Troops being taken ashore in

LCAs. Just said hello to some pals in an LCA passing on the starboard

quarter. It’s a small world. 51st Division still pouring in. More

troop ships than that standing by out to sea. Monitors and Destroyers, which

took part in shelling from further out, standing by, also awaiting orders

from Admiralty.

09.00 We are now at a large bay at east tip of island. The town is on our

port beam and on port bow large fires with dense smoke have started. The

landing beach is sandy, merging into fertile countryside with flat hill in

the distance. Artillery landed sometime before and are now engaging enemy

positions. Circling aircraft are keeping a stout vigil.

09.30 Heavy explosions now occurring regularly on shore. Hands to cruising

stations.

10.45 Bombardment by 6" cruiser and destroyer. Enemy resistance on land.

Aircraft bomb positions. AA fire returned. Ten minutes bombardment.

Amphibians moving in to land. Tanks visible on beach. LCIs still unloading

troops. Other landings reported successful.

15.00 Aerodrome captured. Shelling not required.

15.45 Enemy being shelled in town by 15" monitor. Range accurate. Fall of

shell excellent.

16.00 Rumble of gunfire on ridge from top of island. Heavy fighting

continues. Casualties unknown.

19.55 Bombardment by 6" cruiser to assist our troops.

21.30 Sing song in progress on B gun deck. Ammunition issued to all Marines.

21.45 Moving out of bay to edge of convoy to watch for mines and E boats.

22.00 Air attacks commencing. The sky is lit up like Blackpool

illuminations. Dive bombers attempting to destroy troopships.

22.30 A stick of bombs has just fallen 50 yards astern and ahead and two to

port and two to starboard.

22.45 A large bomb has just dropped on starboard quarter. Bombing is getting

more accurate. Two minor casualties. The Marine Officer has been grazed on

the leg and Yorky was struck in the stomach with a small piece of shrapnel.

None serious.

23.15 No ship appear to have been hit. Smoke clearing away. Two LCIs are

alongside and cannot reach their parent ship.

Sun 11th July

01.00 Shelling by 15" Monitor. Flares on beach.

05.35 Firing with rifles at believed enemy mines and suspicious objects.

Enemy opposition on shore against tanks serious. RM Commandos did splendid

job. Silenced machine gun posts and captured 1,000 Italians.

08.00 Bright sunshine. General clean up of ships. Standing by for further

orders.

The

Sicily landings were successful and we had no

casualties. In the following days we moved along the coast in support of

the advancing army and, by the 16th August, the whole of Sicily was in our hands

and the 8th Flotilla was 'resting up' at Augusta. The

Sicily landings were successful and we had no

casualties. In the following days we moved along the coast in support of

the advancing army and, by the 16th August, the whole of Sicily was in our hands

and the 8th Flotilla was 'resting up' at Augusta.

There was no

rest for the maintenance crew, however, since all main engines were due to have

their cylinder heads removed and overhauled. This involved grinding in twelve exhaust and twelve inlet valves

and refitting 12 fuel injectors on each of 22 engines.

Even with help from the craft motor mechanics and stokers, it was a tough order.

In practice ERAs, OAs, EAs and shipwrights all mucked in

together.

By the 31st August, 1943, we were at Messina in

the north east of Sicily overlooking Reggio on the Italian mainland. The Battleships

were already bombarding the Italian mainland.

On Sept 2nd, we covered landings at Reggio De Calabria. Again no

casualties and 3 days later the whole of Calabria was in our hands. On the

12th September, Italy surrendered and we saw the Italian Fleet pass by to

formally surrender

in Malta. However, with the Germans still occupying the country, the battle for

Italy was far from over.

On the 13th September, half our Flotilla was giving support in the

heavy fighting off Salerno. I was not on this particular operation when one of our craft was hit on the bridge and all Officers and

Coxswain were killed, leaving one Petty Officer, the motor mechanic, to take

command. Together with the Sergeant of Marines, they continued the fight until ordered to withdraw. He then took his craft back to Malta and

received the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal (CGM) for his courageous and

resourceful action.

The whole squadron returned to Dijelli,

where, once more, it was split in two - one half to stay in the Mediterranean

and the other to proceed to Milford

Haven, which included us. We were part of a large convoy and encountered no enemy

on the return journey but, in

very rough weather, five LCTs foundered with the loss of all lives.

In addition, two broke in two but the crews were taken off. Our craft, with their covered

holds, had no problems other than engine breakdowns... I changed craft six times

on the trip to deal with 'big end' failures.

We were diverted to Glasgow, where

all engines were found to be in dire need of major overhaul. Only 11 out of 22

engines were running on all cylinders. Some had scoring of the crankpins, which

prevented the fitting of spare bearings and to allow the engines to operate in

this condition, the pistons on the affected cylinders had been removed, balance

weights fitted to the cranks to prevent excessive vibration, while inlet and

exhaust valves had been fitted to the affected cylinders with telescopic push

rods to stop them opening.

Three weeks after arrival in

Glasgow, the craft had been handed over to Ship Repairers and the Flotilla

disbanded. We were drafted to

HMS Westcliff, at Southend on the south coast of England, for leave and

to await fresh orders.

Preparations

for D-Day

After three weeks leave over Christmas,

1943, I reported back to Westcliff. A week later, I was at Euston Station

in charge of a draft of 30 to form the 332nd Support Flotilla.

This time the Flotilla Officer was a

Lieutenant RN, the Engineer Officer an RNVR Lieutenant, who in Civvy Street was

the engineer in charge of Post Office transport in Scotland. He informed

me, "I don't propose to interfere; maintenance of all craft and supervision of

the maintenance staff is yours." This suited me well and later on he told me he

had pulled strings to get me.

We were to be in

Glasgow until the end of March, so my wife joined me. All the craft were being

fitted with replacement engines by private contractors. My job was to check on

progress in seven different yards on both sides of the

Clyde, stretching from Rothesay to the centre of Glasgow. A lot of travelling was

involved for which we were supplied with a 350 cc BSA motorbike and a jeep.

By

early March, I had a full complement and had been able to pick those I wanted as

my crew. I recruited half of my

old staff, the rest had been drafted elsewhere. At the end of March, I

returned the BSA to the garage and we sailed 500 miles south to

HMS Turtle at Poole in Dorset. Here we commandeered a house near the beach for the officers and later I

found the motorbike at the back. The EO had brought it down, because he thought I

might wish to live at home in Southampton!

In early April, we moved to the Beaulieu

River. The Officers were billeted in Exbury House, the Ratings in bell tents on

the lawn and yours truly at home! At Exbury we undertook daily exercises and carried out essential maintenance until the end of May, when we moved to

the Eastern Docks. These were full of craft and ships of all types and sizes. We

stored our ammunition and supplies to full capacity and on June 4th were ready

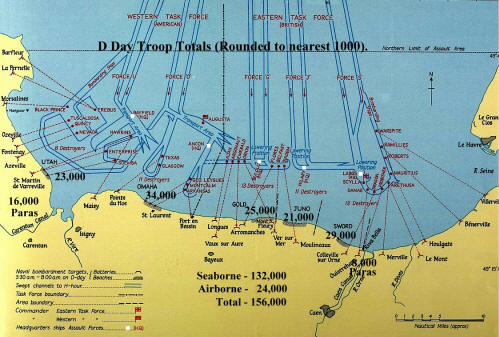

to sail for the invasion of Normandy. We were to leave at 2000, arriving off the

French beaches at 0600 the next morning.

However, the weather was against us and we actually sailed 24 hours later.

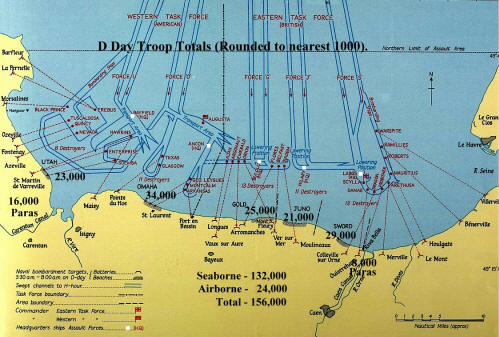

D-Day

and Aftermath D-Day

and Aftermath

It was a rough trip and the

American Mark V LCTs had a particularly hard time. Several of them capsized and quite a few were taken in

tow. They were very small craft, never meant for anything but calm weather.

From one, we picked up our Flotilla Officer from the 8th Flotilla!

At 0400 the next morning, we went

to action stations. We were to go in first, together with the Flak and Rocket Craft, to lay down a barrage

before the troops were landed. We went in line abreast followed by the rocket

craft. Out beyond them were destroyers and cruisers and further out still, two monitors

and HMS Warspite. All opened fire a little after 0500, the noise was

horrendous and morale in the enemy ranks must have dropped to zero.

The landing

craft on our beach had very little trouble at first, although resistance

gradually increased. Bombardment Liaison Officers accompanied the initial

assault troops. Their job was to relay information to

us on targets the Army wanted us to fire on. Our two guns fired continuously from 0500 until 2300,

stopping only when we ran out of ammunition. Thus ended what became known as the "Longest Day" ... and long it was.

After D-day, we spent three days

firing 4 ½ inch shells at unseen targets beyond the beachhead, identified for us

by Army Forward Observation Officers (FOOs) positioned inland.

They reported back on the accuracy of our fire so we could make adjustments to

the range and direction, if necessary. After D-day, we spent three days

firing 4 ½ inch shells at unseen targets beyond the beachhead, identified for us

by Army Forward Observation Officers (FOOs) positioned inland.

They reported back on the accuracy of our fire so we could make adjustments to

the range and direction, if necessary.

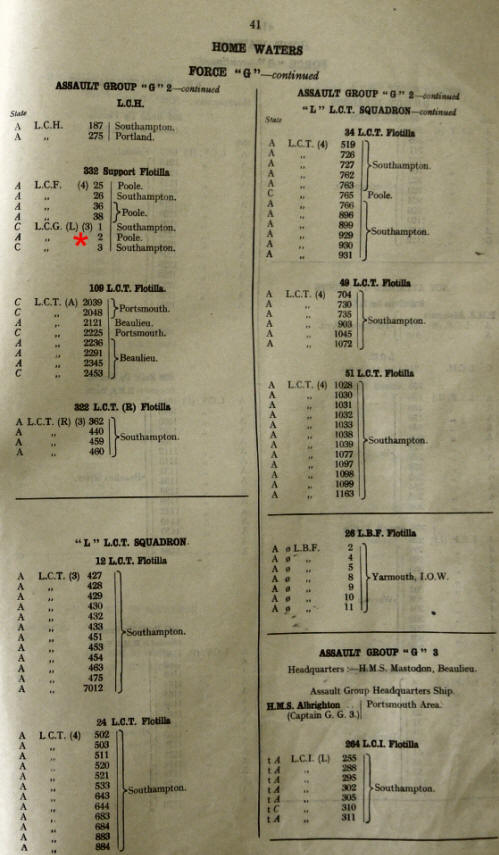

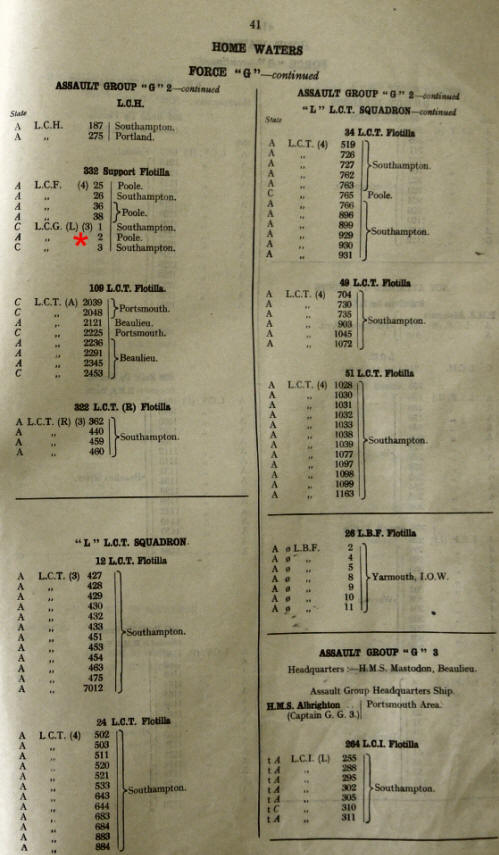

[Extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List'

showing the disposition of LCG 2 just prior to D-Day].

On D + 5, LCG 2, in which I was billeted, was ordered

to go inshore to draw the fire of an enemy shore battery, which had defied the

efforts of the RAF to destroy it. With some trepidation, we weighed

anchor and proceeded inshore firing in the general direction of the battery.

There was no response from the enemy until we made a 180 degree

turn to avoid beaching.

As we headed away from the cliffs, our guns were unable to bear

on the enemy position. Three

explosions followed in fairly quick succession. The first lifted our stern out of the water, the second was a 15"

salvo from HMS Warspite and the third was Warspite's eight 15" HE

shells hitting their target. This battery was mobile, on railway lines and

normally took refuge in a tunnel at the first hint of danger. On this occasion,

as soon as they exposed their position on firing at us, Warspite fired on

the known location of the gun before it could take cover.

The enemy shell had exploded between our rudders, putting our steering gear out of action -

it was impossible to turn the wheel. However, we had been lucky. If the incoming

shell had had twenty feet longer range, I would not be writing this.

Using the main engines for

steering, we put the LCG on the beach

and examined the damage when the tide went out. Both rudders were bent outwards

and since they could not be straightened in situ, we dug deep holes in the sand,

disconnected the rudders and dropped them free of the ship. Meanwhile our signaller tried in vain to

locate a repair ship... but all was not lost. There were many craft on the beach, some of

them apparently damaged beyond repair, so I decided to cannibalise one of them. I rounded up my four ERAs

and some Stokers and set off along the beach.

We had walked about a mile when we

came upon a craft which had the same gear as our LCG 2. She was deserted and

very high out of the water. While the Stokers dug holes in the sand, the ERAs disconnected all the

gear and then, just as we were going to drop the rudders, a voice behind me said,

"What are you doing?" A young RNVR Lieutenant informed me that he was

sailing for Southampton at 0800 the next day. It was now 22.00, so we replaced all the gear and returned

empty handed to our LCG .

We hadn't gone far, when out of

the dark came the challenge, "Halt, who goes there?" I replied, "Friend." "Advance

friend and be recognised." It was a Royal Engineer NCO, who informed me that the

beach was mined and had not yet been swept. The rest of our return journey along

the beach took much longer than expected!

By now the tide had risen, so we turned in

for the night. Next day we received orders from the Senior

Officer to join the evening convoy so that repairs could be carried out in Southampton. At

22.00 hrs, with 14 other landing craft, we

sailed, steering by engines. We should have arrived at Southampton at 09.00 hrs

the following morning but, come daylight, we were alone. However, through the haze we could

see the Isle of Wight and at 10.00 hrs we berthed at Town Quay. An hour later a

tug arrived and took us up the River Itchen to White's Yard.

We subsequently learned E boats had got in amongst the assembled ships and craft and one

of our ships had been sunk. To prevent a repetition, all Flak and Gun ships were

re-assembled as the Support Squadron, Eastern Flank and each night we formed a

protective screen around the ships and Mulberry Harbour. This lasted three weeks,

during which time there were a few sporadic raids. However, by the end of July the army was too far inland

for the squadron to offer support, so we returned to Poole to refit

and to lick our wounds.

Walcheren

- Operation Infatuate Walcheren

- Operation Infatuate

The next couple of months were employed in routine overhaul

and maintenance duties. We were beginning to feel that the war had passed the Support

Squadron by. Then, towards the end of October, we were ordered to prepare 6 LCGs, 6 LCFs, 5 LCT(R)s, together with 6 smaller support craft armed with guns

and smoke mortars and 2 LCG(M) (medium) for a further action.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

We sailed from Poole to Ostend and on October 31st,

we received our orders. D-day was Nov 1st with H-hour 09.45. We were to support the Royal Marine Commando landing at Westkapple on Walcheren,

an island in the River Sheldt estuary. Three heavy warships,

HMS Warspite and the monitors HMS Roberts and HMS Erebus with

their 15-inch guns, were to support us. We

would go in under cover of an aerial bombardment.

The morning dawned cold and miserable with low visibility.

Unfortunately this poor weather was general all over Northern Europe and the RAF was

grounded by fog. The air support, which was an integral part of the original

plan, was not available. However, after a hurried conference, it was decided that

the landing should go ahead. The morning dawned cold and miserable with low visibility.

Unfortunately this poor weather was general all over Northern Europe and the RAF was

grounded by fog. The air support, which was an integral part of the original

plan, was not available. However, after a hurried conference, it was decided that

the landing should go ahead.

The

action started with a bombardment by the heavy ships, whilst the LCGs closed in

on the Westkapple battery with the object of destroying it. However, our 4.7 inch shells

just bounced

off the concrete emplacements. We had been firing for about an hour and a

quarter when the LCT (R)s opened fire. Two of them fired amongst the LCGs and LCFs. LCG 2 and 2 of the LCFs were

damaged. It was my most terrifying experience of the war.

As

the Marines closed on the beach, the enemy batteries opened fire on them and we

were ordered to

draw the enemy fire from the marines. Two LCG(M)s went close in to the beach, No 1 was

literally blown to pieces almost at once. There were no survivors. No 2 was

repeatedly hit by 88mm shells but managed to withdraw, only to sink in deep

water with only six casualties - 2 killed and 4 wounded.

LCG 1 went in with all guns firing and closed to 600 yards, despite being hit three times and set on fire. She was hit several more times

and put out of action. LCG 17 tried to take her in tow but LCG 1 sank. LCG 17

continued to give support but was hit several times and was set on fire. She

was ordered to withdraw. LCGs 10 and 11 were also damaged but continued

in support

until Walcheren was taken on the 8th of November.

Of the 6 LCGs, one was lost and 5 badly damaged. Of the LCTs, 2 were

lost and 3 were damaged and only 2 of the Rocket Craft were undamaged. Of

our crews, 172, had been killed and 204 wounded. However, the enemy fire had been

drawn from the Marines and they were ashore with far less casualties than the support squadron

had suffered.

The cumulative effect of our

firing, including the 15 inch, was to put one gun out of action when a 4.7

inch shell from one of the LCGs passed

straight through the enemy's narrow firing slit. Had the enemy ignored the Support Squadron and

concentrated their firepower on the landings, the Marines were unlikely to have made it.

With the battle over,

we limped back to Ostend, a tired and ragged convoy, some craft under tow, few with

both engines running and all with pumps going flat out to stay afloat. At Ostend, we patched up the

hulls as best we could. Some craft had plates bolted on as it was virtually

impossible to weld mild steel plates to the hulls. On others, cement boxes covered a lot of

the holes. LCG 17 had 47 patches on her hull as she left for Poole.

Following the action, 200 mine sweepers cleared the Sheldt

Estuary and the port of Antwerp was opened to Allied ships - a vital link in

supplying the Allied armies as they advanced towards Germany. Visit

Operation Infatuate for a comprehensive account

of the Walcheren action.

Amphibians (Buffalos) coming ashore at

Westkapelle.

Oranjemolen (Orange Mill) at Flushing (Vlissingen) where No. 4 Commando landed

early on 1/11/44.

French

Commando Officers in Flushing - Lt. Guy de Montlaur, Lt. Guy Hattu,

Commandant Phillippe Kieffer & Lt Jacques Senée.

Bunkers of

the German coastal battery at Westkapelle. The first two are for 9.4

cm artillery and the third for fire direction.

Lt./General

Wilhelm Daser, Commander of the 70th Infantry Division & Fortress

Commander of Walcheren led into captivity accompanied by Major Hugh

Johnston of the Royal Scots.

The Run Down

The Battle of Walcheren saw the end of the war for the Support

Squadron. We stayed at Poole for a few months and then moved down to Appledore

in Devon to lay the ships up in reserve. We spent about six weeks drying out the

engines and pumping around inhibiting oil to prevent rust. This done, we left the

ships and returned to Poole, where we spent the next few months laying up US Tank

Landing Craft on the beach at Arne.

Gradually my staff were drafted away to other jobs

until I was left on my own. I was then absorbed into the Base Staff to maintain

the few landing craft still on the Channel run. Early in July, 1945, I was

advised to stand by to commission a new

Flotilla of LCGs converted from Mark10 landing craft. They were to be 'tropicalised',

so I attended Hall's of Dartford for a refrigeration course, at the end of which

I returned to Poole, but I never did commission the new

Flotilla, since the war ended before they were ready.

The coming of peace brought orders to close some of the Combined

Ops bases, among them HMS Turtle. It took about three months and then I moved up

to Troon and closed down there. Next a draft to HMS Tullicuan, a shore base at

Balloch on

Loch Lomond. Why I was there or what I was supposed to do, I never did find out.

No ships, no small landing craft or even a motorboat and no engine room staff. I

only recall checking through service certificates

and issuing medal ribbons!

By now I was the last Chief ERA in Combined Operations, all the

others having returned to General Service. Many of my old

staff, who were 'Hostilities Only', were being demobbed. I received orders to report

back to RNB Portsmouth on May 31st, 1946. I had been away for three years and

four months. Having spent all this time with none of the usual Naval Bull,

it was with some trepidation that I returned. After three weeks leave mostly playing snooker, I reported to HMS Indefatigable, at

the time the largest of Britain’s aircraft carriers at 28,000 tons and 152,000 HP.

I was about to transfer from the smallest of craft in the Royal Navy to the

largest. I found I had charge of the main engines,

workshops and diesel generators - the latter being Paxmans,

the same as in the LCGs... but all that's another story.

Further Reading

On this

website there are around 50 accounts of

landing craft training and

operations and landing craft

training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page

which can be purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose

search banner checks the shelves of thousands of book shops world-wide. Type in

or copy and paste the title of your choice or use the 'keyword' box for book

suggestions. There's no obligation to buy, no registration and no passwords.

Click 'Books' for more

information.

Acknowledgments

Written by Chief Engine Room Artificer (CERA), Robert

Wallace-Sims. Edited for website presentation by Geoff Slee including the

addition of maps and photos.

|